Getting vaccinated when you’re on immunosuppressive therapy isn’t as simple as showing up at the clinic. For people with autoimmune diseases, organ transplants, or cancer, the immune system is already fighting a losing battle-and vaccines can sometimes fall on deaf ears. But skipping them? That’s even riskier. The real question isn’t whether to get vaccinated-it’s when, and how well it will work.

Why Timing Matters More Than You Think

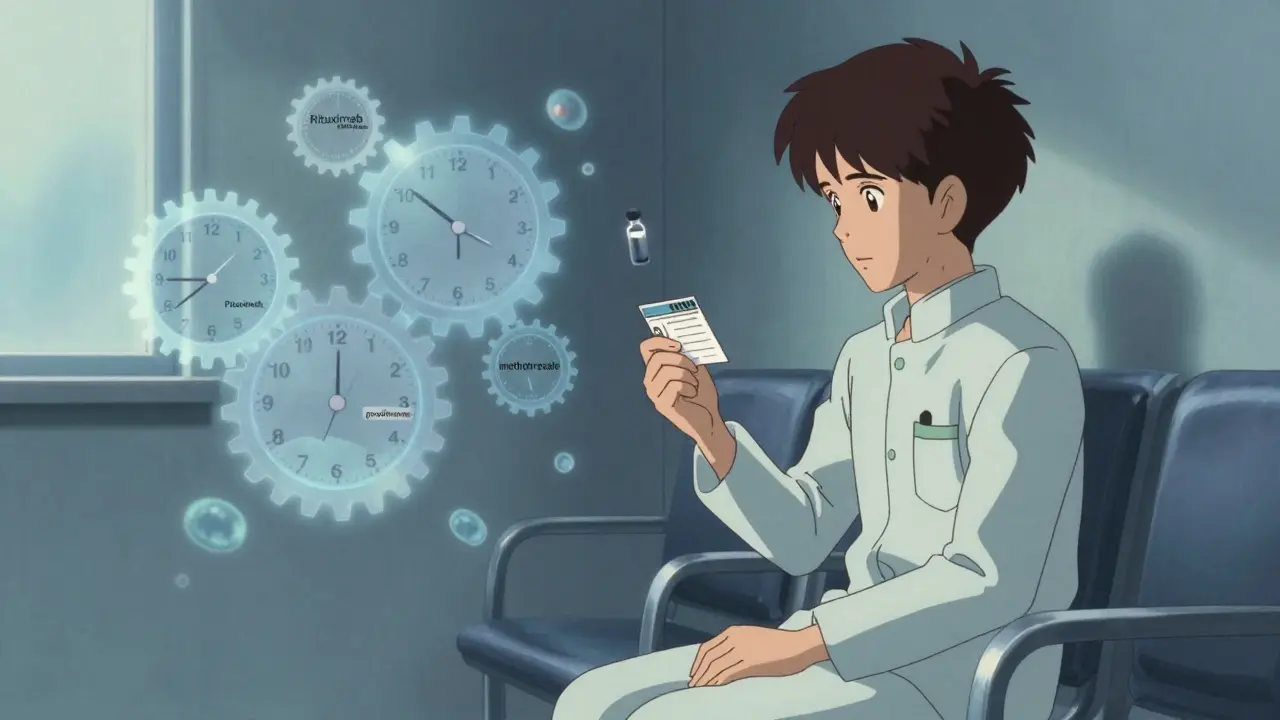

Most vaccines work by teaching your immune system to recognize threats before they cause real harm. But if your immune system is suppressed by drugs like rituximab, methotrexate, or high-dose prednisone, that lesson might not stick. Studies show vaccine effectiveness can drop by 30% to 80% depending on the medication and when you get the shot. For example, solid organ transplant recipients had 56% lower antibody levels after two mRNA COVID-19 doses compared to healthy people, according to CDC data from 2021. The key isn’t just getting the vaccine. It’s getting it at the right time relative to your treatment cycle. A 2023 review from Memorial Sloan Kettering found that patients who got their flu shot within two weeks of receiving rituximab had almost no measurable immune response. But if they waited until their B-cells started coming back-usually 4 to 5 months after the last infusion-response rates jumped dramatically.Drug-Specific Timing Rules

Not all immunosuppressants are the same. Each one interferes with the immune system in a different way, so the timing rules vary.- Rituximab and other B-cell depleters (like obinutuzumab): These drugs wipe out the cells that make antibodies. The safest window is 4 to 5 months after your last dose, and at least 2 to 4 weeks before your next one. Some experts, especially at MSK, recommend waiting 9 to 12 months for the best chance of a response.

- Methotrexate: This common drug for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis can blunt vaccine responses. The American College of Rheumatology advises holding methotrexate for two weeks after getting the flu shot. No need to stop it for other vaccines unless your doctor says so.

- Prednisone: If you’re on more than 20 mg daily, wait until your dose drops below that threshold before getting most vaccines (except flu). High-dose steroids suppress immune memory formation.

- Chemotherapy: For cancer patients, timing depends on your cycle. Some protocols suggest getting vaccines in the week before your next chemo dose, when white blood cell counts are temporarily highest.

There’s no one-size-fits-all. What works for someone with lupus might not work for someone with Crohn’s disease or lymphoma. That’s why personalized timing matters more than rigid rules.

Pre-Treatment Is Best-If You Can

The gold standard is vaccination before starting immunosuppressive therapy. The CDC recommends getting all necessary vaccines at least 14 days before beginning treatment. This gives your body time to build a solid immune memory before the drugs shut down the response. For people planning a transplant or starting biologic therapy, this window is critical. A 2024 IDSA guideline found that transplant patients who got their vaccines ≥2 weeks before surgery had 3 times higher antibody levels than those vaccinated after. But what if you’re already on treatment? Don’t panic. Even delayed vaccines offer protection. A Veterans Health Administration study in 2021 showed that patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunosuppressants still had an 80.4% effectiveness rate against COVID-19 after mRNA vaccination-even with ongoing therapy. That’s far better than no vaccine at all.

What About Live Vaccines?

Live vaccines (like MMR, varicella, or the nasal flu spray) are generally avoided in immunosuppressed patients because they contain weakened versions of the virus. The risk isn’t that they’ll cause disease-it’s that your immune system won’t control them. If you need a live vaccine (say, for travel or childhood catch-up), it must be given at least 4 weeks before starting immunosuppression. Once you’re on treatment, live vaccines are off-limits unless you’re in remission and off therapy for at least 6 months. Always check with your specialist before considering one.Guidelines Don’t Always Agree-Here’s Why

You’ll find conflicting advice across different medical societies. The CDC says get the flu shot ≥1 month after transplant. IDSA says ≥3 months. NCCN says vaccinate whenever you can. MSK says wait 1 month after B-cell therapy or until lymphocyte counts return. Why the confusion? Because the science is still evolving. Most studies track patients for only 60 to 90 days after vaccination. But immunity can take 6 months or longer to fully develop in immunosuppressed people. Also, real-world factors like community infection rates matter. The IDSA guidelines explicitly say: “It’s better to get the vaccine now than to wait for the perfect timing if cases are surging.” In high-transmission areas (over 100 cases per 100,000 people), even patients on rituximab should get vaccinated, even if it’s not “ideal” timing. Protection against severe illness still matters more than perfect antibody levels.

The Bigger Problem: We Don’t Have a Test

Here’s the frustrating part: there’s no blood test to tell you if your immune system is ready for a vaccine. We’re stuck using time intervals because we don’t yet have reliable biomarkers. That’s changing. In January 2024, the NIH launched a $12.5 million trial to test whether measuring CD19+ B-cell counts can predict vaccine response after rituximab. Early data suggests that when B-cell counts rise above 10 cells/µL, vaccine responses improve. But this isn’t standard care yet. Until then, doctors have to guess. And that’s why coordination between your rheumatologist, oncologist, transplant team, and primary care provider is so critical. A 2022 study found that 47% of transplant centers failed to follow optimal vaccine timing-mostly because no one was tracking it.What Should You Do Right Now?

If you’re immunosuppressed, here’s your action plan:- Check your meds. Know exactly what you’re on and how it affects immunity.

- Call your specialist. Ask: “When is the best time for me to get the next vaccine?” Don’t assume your primary care provider knows your treatment schedule.

- Get the current season’s COVID-19 vaccine. Everyone 6 months and older should get at least one dose, even if you’re on therapy. Boosters are recommended every 6-12 months.

- Don’t skip flu, pneumococcal, or shingles vaccines. These prevent common, dangerous infections in immunosuppressed people.

- Ask about T-cell testing. Some labs now offer T-cell response tests after vaccination. They’re not perfect, but they can show if your body responded even if antibodies didn’t rise.

Remember: a weak response is still better than no response. Even if your antibody levels are low, your T-cells might still be fighting off infection. That’s why getting vaccinated-even late-is always better than staying unvaccinated.

Ashley Hutchins

i cant believe people still dont get this why would you wait months to get a vaccine when you could just get it now and maybe live

my cousin got her transplant and waited for the 'perfect time' and ended up in the icu for 3 weeks because she was unvaccinated

you dont need to be a genius to understand that a little bit of protection is better than zero

stop overthinking it and just go get the shot

Lakisha Sarbah

this is actually super helpful i was so confused about when to time my flu shot with my methotrexate

my rheumatologist just said 'get it whenever' and i was terrified i was doing it wrong

glad to see there's real guidance out there

Niel Amstrong Stein

man the more i read about this the more i realize how fragile our immune systems are

we take vaccines for granted like they're just... there

but for people on these meds it's like trying to light a match in a hurricane

and yet we still have to try

the fact that even 80% effectiveness is possible with ongoing therapy is kinda miraculous if you think about it

we're not just fighting viruses we're fighting biology itself

and somehow we're still finding ways to win

❤️

Joey Gianvincenzi

The assertion that 'even delayed vaccines offer protection' is not merely anecdotal-it is empirically substantiated by peer-reviewed longitudinal studies conducted by the Veterans Health Administration and corroborated by the CDC's own surveillance data from 2021. To suggest otherwise constitutes a dangerous conflation of misinformation with medical science.

Amit Jain

you people are so scared of everything

why not just skip vaccines and let nature take its course

my uncle had cancer and refused all shots and lived to 82

maybe your body knows better than some doctor with a clipboard

AMIT JINDAL

i mean i get the whole timing thing but honestly if you're on rituximab you're basically a walking immunological black hole

the science is still so primitive we're just throwing darts blindfolded

they talk about b-cell counts like it's a dial you can turn but we don't even have a proper gauge yet

and don't get me started on how the hell do you coordinate between 5 different specialists who all have conflicting calendars

it's like trying to assemble ikea furniture with no instructions and half the screws missing

and yet somehow we still act like this is normal

we need a centralized immune system dashboard for patients on immunosuppressants

like a one-stop portal that syncs with your meds, labs, and vaccine records

no more emailing 3 doctors and hoping one replies

it's 2024 we have ai for everything else why not this

Ariel Edmisten

get the shot. talk to your doc. don't wait.

Mark Harris

this is the kind of info that saves lives

thank you for breaking it down like this

my mom’s on methotrexate and i finally know what to ask her rheumatologist

Savannah Edwards

i read this whole thing and just cried a little

my sister’s been on biologics for 7 years and every time she gets a vaccine she feels like she’s gambling with her life

she’s always worried she’s doing it wrong, or too late, or not enough

and nobody ever talks about how emotionally exhausting that is

it’s not just about antibodies or timing

it’s about living in this constant state of medical uncertainty

you’re told to be proactive but the rules keep changing

and you’re left feeling guilty for not being perfect

so thank you for saying even a weak response is better than none

that’s the message so many of us need to hear

Mayank Dobhal

lmao this is why i hate medicine

they give you 17 different guidelines and none of them match

my oncologist said wait 3 months, my rheumatologist said 1 month, my pharmacist said 'just get it'

so i got the shot the day after my chemo

and now i'm waiting to die

Marcus Jackson

the NIH trial on CD19+ B-cells is irrelevant. You're still measuring the wrong thing. T-cell immunity is the real marker, and most labs don't even test for it. Also, the 10 cells/µL threshold? That's from a small cohort. You need at least 15 cells/µL for reliable response. I've seen the raw data.

Natasha Bhala

you're not alone

even if your numbers are low

you're still fighting

and that matters more than any lab result

❤️