When a generic drug hits the market, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it works the same way in your body? The answer lies in a carefully designed clinical study called a crossover trial. This isn’t just a routine experiment-it’s the gold standard for proving bioequivalence, and it’s used in nearly 9 out of 10 generic drug approvals in the U.S. every year.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Testing

Imagine testing two painkillers. In a parallel study, one group gets Drug A, another gets Drug B. Differences in results could come from the drugs-or from the people. One group might be younger, healthier, or metabolize drugs faster. That’s noise. Crossover designs remove that noise by giving each person both drugs, one after the other. You’re comparing the same person to themselves. No more guessing if differences come from the drug or the person. This isn’t just clever-it’s efficient. When between-person differences are big (which they often are in real people), a crossover study can cut the number of participants needed by up to 80%. A study that would need 72 people in a parallel design might only need 24 in a crossover. That saves time, money, and reduces burden on volunteers. The U.S. FDA and the European Medicines Agency both require this design for most generic drug approvals. Why? Because it gives the clearest, most reliable signal of whether the generic delivers the same amount of drug to the bloodstream at the same speed as the original. That’s what bioequivalence means: same exposure, same effect.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: AB/BA

The most common setup is the two-period, two-sequence design-called 2×2 or AB/BA. Here’s how it works:- Half the participants get the generic (test) drug first, then the brand-name (reference) drug after a break.

- The other half get the brand-name first, then the generic.

What Happens When Drugs Are Too Variable?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, show huge differences in how they’re absorbed from person to person-even the same person on different days. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs). For them, the standard 2×2 design doesn’t work well. The variability is so high that even with 72 participants, you might still fail to prove bioequivalence. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of just two doses, participants get four: either TRTR/RTRT (full replicate) or TRR/RTR (partial replicate). In TRR, you get the test drug once, then the reference twice. This lets researchers measure how much the drug varies within each person-not just between people. Why does this matter? Because regulators now allow something called reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). Instead of forcing the generic to match the brand within strict 80-125% limits, they adjust the range based on how variable the brand drug itself is. If the brand varies a lot, the generic can vary a little more too-and still be considered equivalent. This is a game-changer for drugs like anticoagulants or epilepsy meds, where tiny differences in absorption can be dangerous. The FDA approved 47% of highly variable drugs using RSABE in 2022-up from just 12% in 2015. Replicate designs aren’t just nice to have anymore. For HVDs, they’re the only reliable path to approval.

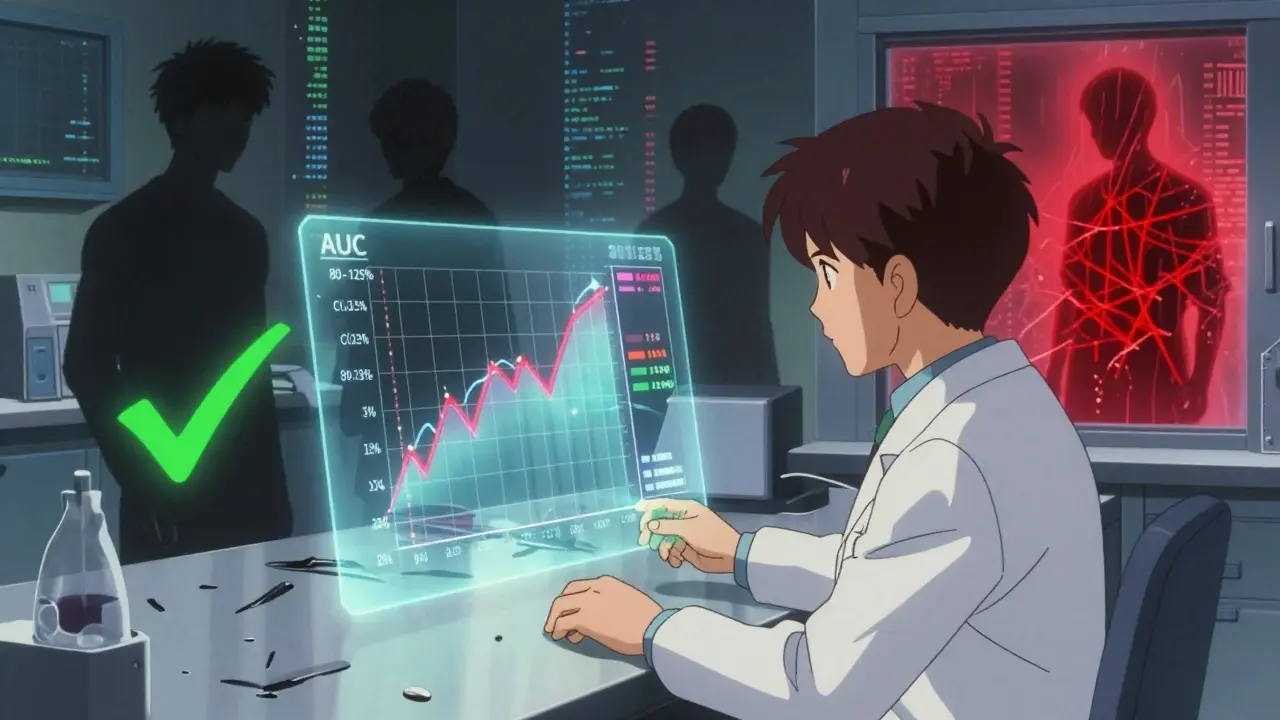

Statistical Analysis: What the Numbers Really Mean

It’s not enough to just give people the drugs. You have to measure what happens in their blood. That means taking multiple blood samples over time after each dose to build a concentration curve. The two key numbers are AUC (total exposure over time) and Cmax (peak concentration). The goal? Show that the ratio of the test drug’s AUC and Cmax to the reference drug’s falls between 80% and 125%. That’s the standard window. But for HVDs using RSABE, the window widens-sometimes to 75-133%. The math behind this uses mixed-effects models in software like SAS or Phoenix WinNonlin. The model checks for three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order matter?

- Period effect: Did time itself change the results?

- Treatment effect: Was there a real difference between the drugs?

Real-World Wins and Woes

A clinical trial manager in 2022 saved $287,000 and eight weeks by switching from a parallel to a crossover design for a generic warfarin study. With an intra-subject CV of 18%, they only needed 24 people. A parallel design would’ve required 72. But another team learned the hard way. They ran a crossover for a highly variable drug with a 42% CV. They guessed the washout period was enough. It wasn’t. Residual drug lingered, skewing the second period. The study failed. They had to restart with a four-period replicate design-costing an extra $195,000. Industry surveys show that 78% of professionals prefer crossover designs for standard drugs. But for HVDs, 68% say replicate designs prevent failure. The trade-off? Replicate studies cost 30-40% more and take longer. But when the alternative is a failed submission and months of delay, it’s worth it.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Regulators aren’t standing still. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows three-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-like digoxin or lithium-where even small differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to make full replicate designs the default for all HVDs by late 2024. Adaptive designs are also rising. Some studies now start with a small group, analyze the data early, and decide whether to add more participants based on what they see. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions used this approach-up from 8% in 2018. It’s not standard yet, but it’s coming. The bottom line? Crossover designs aren’t going away. They’re evolving. As more complex generics enter the market-think biosimilars, inhaled drugs, or long-acting injectables-the need for smarter, more flexible crossover models will only grow.When Crossover Doesn’t Work

There are exceptions. If a drug has a half-life longer than two weeks, waiting five half-lives means months between doses. That’s impractical-and risky for participants. For those, parallel designs are the only option. The same goes for drugs that cause permanent changes in the body, like some cancer therapies or vaccines. Also, if the drug’s effect is irreversible (e.g., a drug that permanently alters a receptor), you can’t give it twice. Crossover fails here too. In these cases, regulators accept parallel designs-but they demand larger sample sizes and tighter controls to make up for the lack of within-subject comparison.What You Need to Know

If you’re a patient, you don’t need to understand the math. But you should know this: every generic you take has been tested in a crossover trial. The system works because it’s designed to catch differences before the drug reaches you. If you’re in pharma, regulatory affairs, or clinical research, here’s the reality:- Use a 2×2 crossover for standard drugs with low variability (CV < 30%).

- Switch to a replicate design for anything with CV > 30%.

- Validate your washout period with literature or pilot data-never guess.

- Use proper statistical models. Don’t rely on simple t-tests.

- Document everything. Regulators audit these studies closely.

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, eliminating variability between different people. This increases statistical power and allows researchers to detect small differences between drugs with far fewer participants than a parallel study would need.

Why is the washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If traces remain, they can interfere with the second treatment’s results, leading to carryover effects. This invalidates the comparison and can cause the entire study to fail. Regulators require at least five half-lives of the drug as a minimum washout.

What is a replicate crossover design, and when is it used?

A replicate crossover design gives each participant multiple doses of both the test and reference drugs-typically four doses across two periods (e.g., TRTR/RTRT). It’s used for highly variable drugs (intra-subject CV > 30%) to accurately measure within-person variability. This allows regulators to use reference-scaled bioequivalence approaches, which adjust the acceptance range based on how variable the original drug is.

What are the FDA’s bioequivalence acceptance criteria?

For most drugs, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) must fall between 80.00% and 125.00% for both AUC (total exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). For highly variable drugs, wider limits-75.00% to 133.33%-are allowed using reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE).

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks), where the required washout period would be impractical. They’re also not used for drugs that cause irreversible effects, such as some cancer treatments or vaccines, because you can’t safely administer them twice.

For professionals, the message is clear: crossover trials are the backbone of generic drug approval. Their structure is precise, their requirements strict, and their impact enormous. Mastering them isn’t optional-it’s essential to bringing safe, effective, and affordable medicines to market.

Lori Anne Franklin

Wow, I had no idea generics went through this much science before hitting the shelf. I always just thought they were cheap knockoffs 😅 But now I get why my pharmacist says they're just as good. Mind blown.

Bryan Woods

The statistical rigor behind crossover trials is genuinely impressive. The use of mixed-effects models to account for sequence, period, and treatment effects ensures that regulatory decisions are grounded in robust data. This level of methodological discipline is what separates evidence-based medicine from anecdotal claims.

Shreyash Gupta

Wait… so you’re telling me the FDA lets generics vary by up to 133%? That’s not bioequivalence-that’s a gamble. 🤔 I’ve seen people switch from brand to generic and get worse side effects. This system is broken. #BigPharmaLies

Ellie Stretshberry

i never thought about how hard it is to test drugs like this. like… people are different and all that. so giving both drugs to the same person makes sense. i just hope they really wait long enough between doses. my uncle took something and got sick because they didn’t wait. 😔

Zina Constantin

This is why I love science-when it’s done right, it saves lives AND money. Crossover designs aren’t just clever, they’re ethical. Fewer volunteers needed, faster approvals, safer meds for everyone. Hats off to the researchers who make this work. 🌍💊

Dan Alatepe

Bro… imagine spending $195k because you guessed the washout period 😭 That’s not a mistake-that’s a whole season of a Netflix drama. One wrong number, and your whole year goes up in smoke. Pharma ain’t no joke.

Angela Spagnolo

I really appreciate how detailed this is… but… I’m still a little nervous about the 80-125% range… what if it’s on the edge?… like… what if it’s 79.9%?… does that mean it’s unsafe?… I just… I want to know it’s 100% safe…

Sarah Holmes

Let me be perfectly clear: this entire regulatory framework is a dangerous illusion. You cannot measure human physiology with confidence intervals. The body is not a lab rat. The FDA’s obsession with statistical compliance has blinded them to the lived reality of patients who suffer when generics fail. This is not science-it’s corporate sanitization of risk.

Jay Ara

good breakdown man. i work in a clinic and patients always ask why their generic feels different. now i can tell em it’s probably the washout or the cv. just make sure they dont skip doses and keep track of how they feel. small things matter.